Liverpool Biennial, World Refugee Week, Windrush 75

A glut of events and occasions that demand attention and thought | Migration | British Empire | Colonialism | Cultural erasure | Names | uMoya: The Sacred Return of Lost Things

I recently wrote about mapping the world and the global reach of the British Empire, and I guess this letter is on the same theme - migration.

Whether voluntary or forced it is in the forefront of my thoughts this week (and generally given my personal family history).

I wrote something about the 2023 Liverpool Biennial (the link will be added here when it is published online by the commissioning organisation), and the whole experience took me back to so many strands of personal and public history.

The biennial also reminded me of when I first got involved with the Liverpool arts scene.

In 2018 I was one of the Artists in Residence for the Liverpool Independents Biennial Festival.

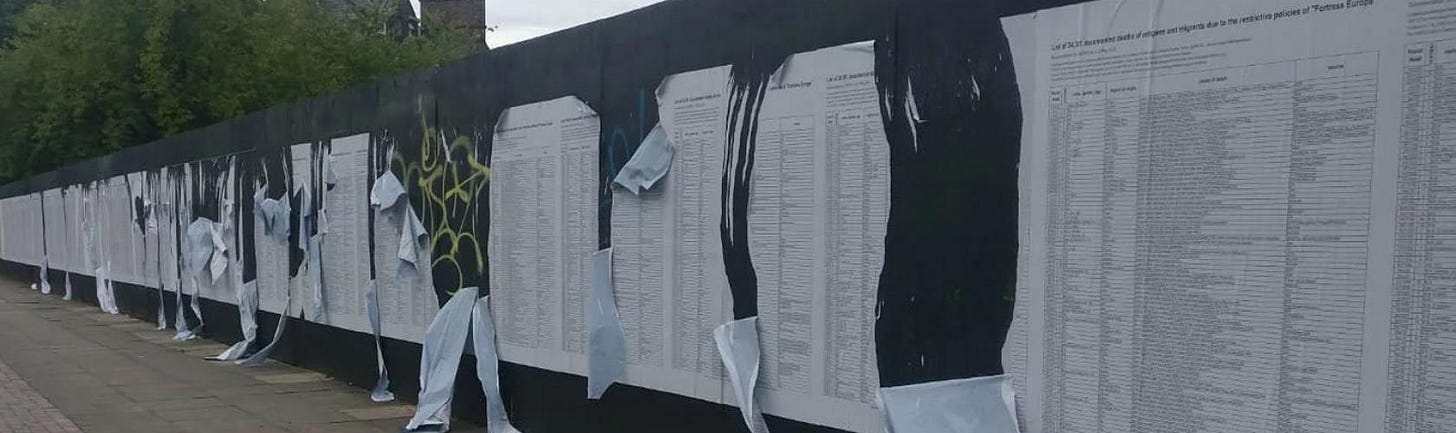

This was the year that The List by Banu Cennetoğlu was displayed on Great George Street, Liverpool: The List is a record by UNITED for Intercultural Action, of all known refugees who have died while trying to migrate to safety in Europe - at that time the number stood at 34, 361.

They recently updated the documented cases of migrant and refugee deaths (since 1993) due to the Fatal Policies of Fortress Europe - the number stands at: 52,760 deaths as at 01 June 2022.

In 2018 I was so shocked by the enormity of The List, and the people behind the statistics, that I wrote a play about it as part of my Artist Residency. The Thin Red Line was shown, in its development phase, at Hope Street Theatre, Liverpool with the Director of UNITED, Geert Ates, in attendance from Amsterdam, Netherlands for the show and a Q & A afterwards.

The play was published in Post It: Independents Biennial Writers-in-Residence (2018) a response to the festival, described as “an outstandingly accurate reflection of the festival it set out to document.”

Read reviews and feedback here.

Some of the background to one of the family stories in my play can be found here.

During the 2018 Liverpool Biennial The List by artist Banu Cennetoğlu, in conjunction with UNITED for Intercultural Action, was repeatedly vandalised.

The title of the 2018 Liverpool Biennial was: Beautiful World, Where Are You?

The question still needs an answer in 2023.

Mentioned in my end of year review for 2022, I bring you this gem again: The Swimmers (2hr 15m)

The European governments, especially the UK, malign refugees and asylum seekers, yet do not provide safe routes of travel.

Watch this gripping film, based on true life events of Yusra and Sarah Mardini, and you will feel immersed in the reality of profound loss of family, home, and national identity.

The current Liverpool Biennial is titled : uMoya: The Sacred Return of Lost Things; in the isiZulu language, ‘uMoya’ means spirit, breath, air, climate, and wind, and the curated art responds to these meanings; it runs from 10 June to 17 September 2023.

This festival made me think of remapping, reversing the historical colonial lines drawn to divide and separate, and the attempts to regain what was lost.

It it a chance to pause and reflect for a moment, and the port city of Liverpool, is ideally placed to further acknowledge its association with the human trafficking that colonialism condoned and promoted.

The festival hub is based at the Tobacco Warehouse, Stanley Docks situated at the edge of the River Mersey.

This imposing structure is the largest brick built building in the world that was once used to store vast quantities of tobacco, rum and other commodities, when Liverpool was at its trading apex as the one of the largest ports in the UK (along with London, Bristol and Glasgow) involved in the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade: human trafficking of Africans.

The Victorian Tobacco Warehouse, constructed mainly of bricks with iron pillars in the interior, remains a monumental local and national signifier to Liverpool’s pivotal role in the global migration that was an African Holocaust.

During this time many Africans had their names forcibly erased, languages, cultures, families were lost and separated by sea and land, histories were rewritten, and natural resources stolen and placed in the coffers of the British Empire.

The Liverpool Biennial Festival has the potential to be a portal to a place of healing, a place of learning, also a place of discomfort, and yet a place of hope.

It may be the gap in time where we together can start the return of what was lost.

If possible, please visit uMoya: The Sacred Return of Lost Things.

If you can’t do that, please download the festival guide and maybe partake of the art and commentary from there.

While Windrush celebrations are gathering momentum, I am pausing a while to do more reflection on the whole government handling of Black citizens from the Windrush generation who have been badly treated, as second or even third class citizens.

Even today, as I write this, a new item has been brought to my attention regarding the illegal and immoral deportation of hundreds of mainly Caribbean people suffering from chronic illness, and mental health illness.

Added to the ongoing Windrush Scandal, there is little to celebrate bar our resilience in the face of this never-ending onslaught of discrimination.

I wish I did not have to celebrate having so much resilience because it grows from repeated trials.

So, this month of June already has so many points for discussion and action. It’s going to be a busy year going forwards.

I will be shortly publishing a collection of my own words and thoughts on Windrush 75.